Want to scale your innovation? Start by mapping your value network

How understanding the players in your game can help you scale successfully

There comes a time in innovation when you realise you might have taken on something a bit too big. No matter how hard you throw yourself into the challenge, creating value from your idea is going to need a little help. Changing the world, or even a small piece of it, takes a lot of push. That’s the moment when you realise you need ‘complementary assets’ – the ‘who else?’ and ‘what else?’ pieces of your innovation jigsaw puzzle.

It's a challenge at the very beginning – how to put together a network of people and resources to bring your idea to life? But it’s an even bigger challenge when it comes to scaling innovation – how to get widespread adoption of your ‘best thing since sliced bread’ innovation.

Something which Otto Rohrwedder, the inventor of sliced bread (or more precisely the machine which enabled it) came to understand. He spent fifteen years working to develop and scale his invention and set up the Mac-Roh Company to launch his great idea. Only to see it arrive with more of a whimper than a bang. The bakers to whom he tried to sell it were underwhelmed. They thought the machine too complex for everyday production, it was bulky and took up precious space – and they weren’t convinced of the need anyway. Teetering close to the edge of bankruptcy he persuaded a local baker, Frank Bench, to invest and install the first machine.

On July 7, 1928, the first loaf of commercially sliced bread was produced by the Chillicothe Baking Company of Missouri and sold under the brand name Kleen Maid. And while bakers had been sceptical of the benefits local families in the mid-West were much more enthusiastic. As a review in the local newspaper (the Constitution Tribune) put it:

“So neat and precise are the slices, and so definitely better than anyone could possibly slice by hand with a bread knife that one realizes instantly that here is a refinement that will receive a hearty and permanent welcome.

Within two weeks bread sales from the bakery had increased by 2000%! The idea began to take off across the country and two years later the New York-based Continental Baking Company began using Rohwedder’s machines to build an entire business around sliced bread. Their product – Wonder Bread – (and the accompanying marketing campaign) helped lift awareness to a high level. By 1933 almost every bakery in the USA had a slicing machine and 80% of the bread produced in America was sliced

Otto isn’t alone; many innovations which ultimately scaled successfully spent a long time in the doldrums, great ideas which drifted because of the lack of partners to give the required momentum. J. Murray Spangler’s invention of the electric vacuum suction sweeper nearly wheezed its last before it could make it into everyday home use. It was only when he connected with William Hoover that the venture took off. Mark Twain’s enthusiasm for the typewriter was that of an early adopter but the only way Christopher Sholes and his colleagues could get their machine to a widespread market was by teaming up with the experience of the Remington company who understood mass production, marketing, logistics and all the other ‘complementary assets’ they needed to scale their innovation.

And Earl Tupper’s brilliant bit of alchemy in turning black sludge waste from oil wells into brightly coloured polypropylene storage vessels signally failed to impress American families until the link-up with Brownie Wise who brought her social marketing skills literally to the party. Home demonstrations via a social get-together not only accelerated sales but also laid the foundation for a powerful new addition to the marketing repertoire.

So scaling innovation is a multi-player game. We’ve learned that to create value at scale needs a network – but importantly one which goes beyond the sum of its parts. Systems have ‘emergent properties but these only emerge if there is an organizing energy to enable the process. And they need to share a common purpose, reflected in the current discussion of innovation ‘ecosystems’ , a concept which comes originally from biological science and refers to “the complex of a community of organisms and its environment functioning as an ecological unit”

It's been applied in many branches of natural science with the same focus on an interdependent collection of elements with a shared goal or purpose, for example in geography:

An ecosystem is a geographic area where plants, animals, and other organisms, as well as weather and landscape, work together to form a bubble of life… Every factor in an ecosystem depends on every other factor, either directly or indirectly. (National Geographic Encyclopedia)

It’s pretty clear that ecosystems don’t just happen; in the physical world they take millions of years to settle into a viable pattern. And in the world of organisations it’s going to involve much more than just assembling a set of components. It will need active management to secure the emergent properties.

Systems of this kind aren’t just a challenge in the world of commercial innovation. In fact social innovation – making changes to create a better world – requires even more attention to assembling ecosystems which create value. Take the World Food Programme, one of the agencies within the United Nations which tries to help deal with the severe and age-old challenge of making sure people get enough to eat. They have a long history of innovation and recent examples include the Optimus programme which aims to improve efficiencies on the supply-chain which eventually makes it possible to feed a hungry child – or not. Optimus uses digital tools to help, and it worked as an effective pilot project back in 2015 in Iraq. But scaling it required many players coming on board and working together, not least national governments. Thankfully the results have moved the needle in the right direction; Optimus now operates in 20 countries including Ukraine, Yemen and Syria, reaching close to 7.5m beneficiaries and with efficiency savings (which equate to more effective food relief) running at over $50m.

So ecosystems matter in the innovation journey to scale. Which introduces three challenges for innovators:

· How to find complementary partners?

· How to form them into a coherent value network?

· How to get that value network to perform as an ecosystem?

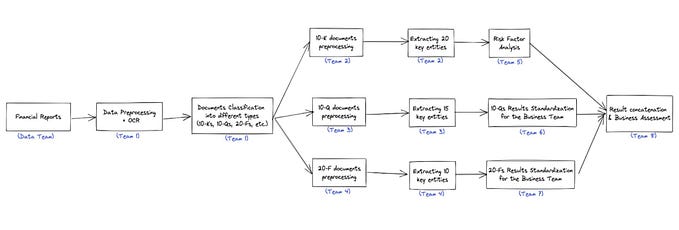

All three of these rather depend on having a good understanding of who ‘they’ are and the different roles they play. So we need a map and a way of charting our journey to scale using it. We’ve developed a model for our new book about scaling innovation which identifies 9 core roles which entities in a value network can play:

· Value creators are those who develop new value – the innovators. This can be one organisation, a partnership or joint venture, or it can be done across a distributed network. The key aspect of this creation is that it is new value.

· Value consumers are those who consume the value which our system creates. Although we often talk of ‘the market’ we should remember that such ‘markets’ are often multi-layered. Our innovation might be used by individuals, businesses, organisations or governments. For many products and services, those who gain value from it may not directly purchase it – that’s often the case with public services like education or health.

· Value captors - so far this looks a simple enough story – value being created and consumed. But there’s another key role here which is occupied by those who capture value from the innovation not by using it, but by being a part of it.

This is where the entrepreneur takes their profit from the risks they have expended. It is investors in the company which launches and sells the product or service. And it’s all the other supply-side players whose complementary goods and services link together to create the offering.

We need these different players to be part of our value network, our ecosystem. But we also need to recognise that they need an incentive – what’s in it for them? Importantly this doesn’t have to be a financial gain or reward – it could also be an investment in learning new approaches or accessing new markets or it could be about reputation and social identity. Think about the brand-building possibilities for companies which help scale social innovations as part of their ESG story.

These 3 entities are ‘bookends’ – the principal players in the value process. But there’s a second set of roles played by ‘movers’ – those entities which enable the process ot happen. These include:

· Value conveyors are players actively involved in the process of adding value to how our solution comes into being and how it is experienced by consumers. Essentially, the value of the innovation grows through the activities they perform. They are more than just channels: their actions actually increase the value of the innovation itself, be it a product or service. Conveyors might be supply side partners upstream or marketing and distribution partners downstream; either way we need them in our ecosystem to ensure value gets created and moved to where it can be consumed.

Brownie Wise’s performances at Tupperware parties were the stuff of legend. She had all sorts of tricks including throwing a container full of tomato soup across the room to demonstrate the strength of the seal (no messy carpets). But her real contribution to the success of the brand was in the role she played as a conveyor, mobilising an army of other women to act as demionstrators and sales agents across the country.

· Value channels are passive in the sense that, like roads or railways, they exist as infrastructure but are independent of the nature of the traffic using them. They are important, necessary elements in scaling but they are not sufficient to assure scale. If they weren’t present or if they are disrupted then value movement couldn’t take place, but they are not active elements in the value creation process. It’s important to think about them not least to explore dependences and how alternatives might be brought into play.

Think about the huge impact to global value flow when the container ship Ever Given got stuck in the physical channel of the Suez Canal for a week back in 2021! Or the way in which the containers on that ship represented a revolution fifty years earlier in the way that the channel of intermodal transportation (road/rail/sea) operated – Malcolm McClean’s innovation of containerisation literally changed the world.

· Sometimes there is a role for value coordinators to help to make connections and bring different players together to enact value. For example, a department store offers a physical space in which multiple value creators can connect with value consumers; street markets and large-scale shopping malls offer a similar opportunity. Today’s platform businesses like Alibaba, Amazon or Apple build on this model, providing ‘digital department stores’ across which millions of transactions can take place between creators and consumers.

A third group of players in our value network are those we call ‘shapers’ – because they do just that. They shape the potential amount of value that can be created, consumed, moved and captured within a value network.

· Value cartographers are the ones who make the maps; they play key roles in structuring a market and determining how much value is possible within a value network. Examples might be regulators, trade unions or influential umbrella organizations. Cartographers can play a major role in accelerating – or slowing – the journey to scale. Think about the current moves towards scaling electromobility; much of the journey to scale will be influenced by the regulatory roadmap. Policies like subsidies or tax relief on electric vehicles, or those which militate against fossil fuels, will provide acceleration – for example, the UK has a target of no new cars running only on fossil fuels by 2035. Equally, legislation to ensure compliance can slow down scaling possibilities – think about the EU’s stance on genetically modified organisms which has acted as a brake on investment and exploration of this technology.

· Value competitors compete with us for the attention of value consumers. They might be direct competitors offering a similar product or service or they might be indirect competitors – for example Netflix is not only in competition with other streaming services but with other ways in which people might allocate their attention– reading, sleeping, looking at their partner while having a conversation. The important thing is that these competitors all shape the context in which value creation/consumption can take place.

· Lastly we have value complementors – entities which complement the value an innovation offers. Sometimes they are essential: Thomas Edison’s attempts to revolutionise domestic lighting arrangements depended on having something (an electricity supply) into which users could plug his new light bulb innovation. Bluetooth devices like intelligent earphones depend on having the technology available and operating to a common standard.

So nine different roles which may be present in a value network. Some are obvious – for example, we clearly need a value creator and a value consumer to bookend our model. But even here the lines can blur. Consumers can also play a role as creators – think about what Lego has done with its efforts to engage users as co-creators. GiffGaff is a small but highly successful player in the tightly competitive world of mobile phone networking; its excellent customer service record is in no small measure down to the way in which it has engaged its community of consumers to play this role…

And some are less obvious but important. Take cartographers and the ways in which they can make or break scaling efforts. Mobile money is still an exciting new field for apps and hardware players – yet it’s been a reality in east Africa for over a decade. M-PESA has been a transformational innovation and has scaled around the world – but its early success depended critically on the support of the central bank rather than its opposition to newcomer ideas. It helped create a fertile regulatory landscape within which mobile money could develop and scale.

Sometimes these roles are emergent – for example the TV and movie industry is increasingly interacting with fans who organize themselves into active communities whose activities and opinions can influence (for better or worse) the scaling possibilities of a core offering. Think about the role played by the ‘Star wars’ community with its conventions, costumes and huge online presence. This is not directly controlled by the film companies but instead exists alongside it, complementing the rate and direction of development. Fans of this kind increasingly play a role in creating new characters and backstories for fringe players who later make it to the mainstream of the media offerings – think about some of the Star Wars spin-offs. Robert Jenkins work atMIT has been tracking the huge influence such fandom has on innovation in the creative industries.

It’s useful to think in terms of the different roles we need and how they might interact, first to help us in our hunt for finding partners. But we also need to form them into viable ecosystems – each system has different configurations but drawing a system boundary is a good starting point. Then we have to work with them to create high performing ecosystems – and this is where the work really starts. It’s about creative relationship building, getting to win-win partnerships.

Which is another story, one which we’ll follow up in a future post.

You can find out more on the model and our approach in ‘The scaling value playbook’, published shortly by de Gruyter.

If you’ve enjoyed this story please follow me — click the ‘follow’ button

You can find a podcast version of this here

If you’d like more songs, stories and other resources on the innovation theme, check out my website here

Or listen to other episodes of my podcast here

And if you’d like to learn with me take a look at my online course here